A WannaCry-inspired DFIR lab (safe simulation) with FortiGate

A portfolio DFIR case study: simulate ransomware-like activity safely, capture disk + memory, analyze with Autopsy/Volatility, and contain lateral movement with FortiGate.

Blog

These posts are part lab notebook, part “how I’d explain this to a busy engineering manager or CISO.” Everything here is safe to share, but still grounded in real technology and real work.

Post #9 · · DFIR / Home Lab

A portfolio DFIR case study: simulate ransomware-like activity safely, capture disk + memory, analyze with Autopsy/Volatility, and contain lateral movement with FortiGate.

Post #8 ·

I deployed Cowrie behind a FortiGate VIP, then monitored live sessions with FortiView and exported logs to FortiAnalyzer.

Post #7 · · Home Lab / Network Security

A baseline capture turned into a quick DNS-beaconing investigation — and a permanent upgrade to how I monitor my home lab.

Post #6 · · Windows / Security

Reproducing a “classic” Windows misconfiguration, separating signal from noise, and why exploitability depends on the surrounding posture.

Post #5 · · Entrepreneurship / Defense Tech

Customer discovery, rapid pivots, and what it feels like to pressure-test a DoD patent into a real product narrative.

Post #4 · · Home Lab / Virtualization

I tried ESXi, pivoted to Proxmox VE, fixed a broadcast-IP mistake, and got my first Kali VM running smoothly (VirtIO, QEMU agent, and a few package-signing lessons along the way).

Post #3 · · Home Lab / Network Security

I moved smart-home devices onto an isolated SSID, tuned 2.4 GHz settings for legacy clients, and built deny-by-default firewall rules with explicit allowlists for only what IoT actually needs.

Post #2 · · AI / Lab

Notes from running local models on my laptop and in the cloud — and why spinning up a GPU sometimes feels simpler than “productivity” software.

Post #1 · · Story

My first sales role, no experience, a flat territory, and how obsessing over real inventory and pricing data unlocked growth during COVID.

Post #9 · · DFIR / Home Lab

I ran this on Proxmox with multiple VLANs to prove segmentation and containment decisions using FortiGate verification (sessions/logs/debug tools).

The primary control tested was a default deny for SMB (TCP/445) from USERS → SERVERS. This reduces a common ransomware

lateral movement path (file shares, admin shares, and “server hunting” over SMB).

config firewall policy

edit 10

set name "Deny-SMB-Users-to-Servers"

set srcintf "VLAN10"

set dstintf "VLAN20"

set srcaddr "all"

set dstaddr "all"

set action deny

set service "SMB" # TCP/445

set schedule "always"

set logtraffic all

next

endInstead of relying on ad-hoc session commands, I verified SMB blocking using FortiOS session-table filters and debug flow output.

1) Session-table check (expected: no established SMB sessions)

diagnose sys session filter clear

diagnose sys session filter dport 445

diagnose sys session list2) Real-time proof (debug flow)

diagnose debug reset

diagnose debug flow filter clear

diagnose debug console timestamp enable

diagnose debug flow show console enable

diagnose debug flow filter addr 192.168.10.10

diagnose debug flow filter port 445

diagnose debug flow trace start 50

diagnose debug enable

# (trigger an SMB attempt now)

diagnose debug disable

diagnose debug resetOptional quick validation (packet sniffer)

diagnose sniffer packet any "host 192.168.20.10 and port 445" 4 0 aRather than running live malware, I used a harmless simulator to generate measurable artifacts and network telemetry:

.encrypted copies of test files# RansomwareSimulator.ps1 (safe simulator)

$testPath = "C:\Users\Public\TestFiles"

$share = "\\192.168.20.10\share" # adjust to your lab share

# 1) Generate SMB telemetry (safe): attempt to access the share

try {

Get-ChildItem -Path $share -ErrorAction Stop | Out-Null

Write-Host "SMB access succeeded (unexpected if deny policy is active)."

} catch {

Write-Host "SMB access failed/blocked (expected in this lab)."

}

# 2) Generate “encryption-like” artifacts (safe): copy files to *.encrypted

$testFiles = Get-ChildItem -Path $testPath -File -ErrorAction Stop

foreach ($file in $testFiles) {

$encryptedFile = "$($file.DirectoryName)\$($file.Name).encrypted"

Copy-Item -Path $file.FullName -Destination $encryptedFile -Force

Start-Sleep -Milliseconds 100

Write-Host "Encrypted (simulated): $($file.Name)"

}I acquired evidence and analyzed it on a separate analysis VM (never analyze on the “infected” box). Since the victim was a VM, disk acquisition was done in a VM-centric way (snapshot/export/clone) and then hashed.

Example hash step (analysis VM)

sha256sum /mnt/analysis/victim_disk.imgFor a Windows victim, I used a Windows memory acquisition tool (e.g., WinPmem/DumpIt or equivalent) and then hashed the resulting dump.

Get-FileHash -Algorithm SHA256 C:\memory_dump.rawAutopsy was used via the GUI workflow:

.encrypted to find simulator artifactsVolatility was used to identify suspicious execution context (process list + command line) and to review network artifacts where supported.

volatility -f C:\memory_dump.raw windows.pslist

volatility -f C:\memory_dump.raw windows.cmdline

volatility -f C:\memory_dump.raw windows.netstatA firewall policy doesn’t “move” a host to another VLAN. To quarantine a workstation in a lab, use one of these realistic methods:

Post #8 ·

As part of my cybersecurity research and hands-on network security projects, I built and tested a honeypot using a FortiGate firewall. The goal was to simulate a vulnerable system that could attract and log unauthorized access attempts — without exposing my internal network.

Step 1: Deploy the honeypot (Cowrie)

Cowrie was installed on an Ubuntu VM with IP 192.168.100.10. Installation steps:

sudo apt updatesudo apt install git python3-venv python3-pip -ygit clone https://github.com/cowrie/cowrie.gitcd cowriecp cowrie.cfg.dist cowrie.cfgpython3 -m venv cowrie-envsource cowrie-env/bin/activatepip install --upgrade pippip install -r requirements.txt

bin/cowrie start

Step 2: Configure a FortiGate Virtual IP (VIP)

I mapped a public-facing IP to the honeypot’s internal IP:

config firewall vip edit "honeypot-vip" set extip 203.0.113.5 set extintf "wan1" set mappedip "192.168.100.10" nextend

Step 3: Allow external access via a firewall policy

config firewall policy edit 100 set name "Allow-Honeypot" set srcintf "wan1" set dstintf "internal" set srcaddr "all" set dstaddr "honeypot-vip" set action accept set schedule "always" set service "ALL" set logtraffic all nextend

From my Kali Linux VM (192.168.100.25), I attempted to SSH into the honeypot VIP:

ssh root@203.0.113.5

Cowrie captured and logged the attempt and created a TTY log for later review:

2025-12-20 13:22:01+0000 [SSHChannel session (0) ...] Opening TTY log: log/tty/20251220-132201-7e9a.log

To monitor live sessions in the FortiGate CLI:

diagnose sys session list | grep 192.168.100.10

To ensure traffic logging was enabled:

config log setting set status enable set logtraffic start-stopend

From there, I reviewed connection attempts in FortiView and exported logs to FortiAnalyzer for correlation and longer-term analysis.

The honeypot successfully attracted SSH probes and basic scans. All actions were recorded without endangering the internal network, and I validated end-to-end visibility from inbound policy hits to honeypot-level command logging.

This project sharpened my FortiGate CLI skills and gave me practical experience with threat emulation, packet logging, and network deception techniques. It’s a strong addition to my cybersecurity lab portfolio — and a foundation I can extend with FortiAnalyzer/FortiSIEM integrations over time.

Post #1 · · Story

When I first joined United Hose Inc., I didn’t come from a traditional sales background. No polished script, no massive Rolodex, no secret list of “accounts ready to buy.” I did what everyone around me seemed to be doing — cold calls, email blasts, following up on stale leads — and it felt like shouting into the void.

The pressure was real. Numbers needed to move, and “try harder” wasn’t a strategy. I knew if I just kept doing the same surface-level outreach, I’d get the same surface-level results.

Instead of only acting like a salesperson, I started thinking like a customer. If I were running a shop, what would I actually care about? Price, sure — but also who has stock today, who can deliver when things break, and who understands my world enough not to waste my time.

So I started calling the people who were selling to my customers and prospects every day. I asked the kinds of questions a real buyer would ask: what’s on the shelf, what’s moving, and what it costs out the door. Over time, those calls turned into something valuable: a living database of what the market really looked like — not just what a spreadsheet said it should look like.

Map loads when you open this post. Pins highlight the markets I focused on most.

I started tracking everything. If a competitor was consistently pricing a certain hose at one level, and I knew our cost structure and service was strong, I could be intentional about where to undercut, where to match, and where to walk away.

This wasn’t about racing to the bottom; it was about being precise. Instead of “we’re cheaper,” I could have targeted conversations: “On these five SKUs, I know I can save you money without sacrificing quality or lead time. Let’s talk about those first.”

That role at UHI was my first real sales job, and watching the numbers move because of a system I built gave me a huge confidence boost. It showed me that I didn’t need to be the loudest person in the room; I just needed to be the most curious about how the system actually worked.

Eventually, that mindset pulled me toward tech. I joined a startup focused on helping manufacturers turn downtime into something they could actually measure and plan around — not just complain about after the fact. The same pattern showed up again:

Looking back, UHI was where I learned that data, curiosity, and empathy for the customer can beat a polished script. That lesson still shows up in how I approach networking, security, and every “this is how we’ve always done it” conversation I run into.

Post #4 · · Home Lab / Virtualization

I wanted to bring an older server back to life as a small home lab: a hypervisor I could trust, a place to run security VMs (Kali, Ubuntu), and enough flexibility to experiment without constantly rebuilding the base OS. The end state was simple: clean virtualization, predictable networking, and a workflow that feels “lab-ready.”

My first attempt was VMware ESXi. I hit friction immediately: I grabbed a ZIP instead of a bootable ISO, Rufus didn’t like it, and the “right” way forward involved building a custom installer image. ESXi is powerful — but for a quick home-lab build, the workflow felt heavier than I needed.

Proxmox was the opposite experience: download the ISO, make a bootable USB, install, and you’re online. The high-level steps were:

F11 or Del).

During install I initially configured the host IP as 10.0.0.255.

That failed because .255 is typically reserved as the broadcast

address in a /24 network. I corrected it to:

10.0.0.10/24, with gateway 10.0.0.1 and DNS set to a

public resolver.

.0 and .255 host

addressing on common subnet sizes — it’s an easy mistake that breaks connectivity fast.

After reboot, the Proxmox web UI came up on port 8006:

https://<server-ip>:8006. The default login pattern is

root with the Linux PAM realm. The interface is

straightforward — and that’s where the build stopped feeling fragile and

started feeling operational.

Once the host was stable, I uploaded the Kali ISO to the Proxmox storage and created a VM with a modest baseline:

During install, GRUB asked for a target device; selecting the primary

disk (/dev/sda) completed the setup cleanly.

The first boot was usable but sluggish. A few Proxmox-side changes made a noticeable difference:

q35).

Two issues were common “first-lab” pain: package signing keys and third-party repos.

For an apt GPG key error like:

NO_PUBKEY ED65462EC8D5E4C5, I imported the missing key from a keyserver.

sudo apt-key adv --keyserver keyserver.ubuntu.com --recv-keys ED65462EC8D5E4C5

apt-key is deprecated on newer Debian/Ubuntu releases, but it can still

be useful for quick lab troubleshooting. Long-term, prefer keyrings under

/etc/apt/keyrings.

For Docker installs, I added Docker’s official repository to avoid outdated packages:

curl -fsSL https://download.docker.com/linux/ubuntu/gpg | sudo apt-key add -

sudo add-apt-repository "deb [arch=amd64] https://download.docker.com/linux/ubuntu focal stable"

Proxmox is stable, Kali is running with a responsive GUI, and the next step is adding an Ubuntu VM to host local LLM experiments and Docker apps. The bigger win is that I now have a repeatable process: I can build, break, fix, and rebuild quickly — which is exactly what a good lab is for.

Post #2 · · AI / Lab

AI is everywhere, but most of it lives behind someone else’s API key. That’s fine for some use cases, but as a security-minded person—and occasionally a CISO—I wanted to see what it felt like to run models closer to home: either on my own machine or on infrastructure I could trust.

I assumed it would be hard. “Local LLMs?” I thought. “That’ll involve compiling code, wrestling with Docker, and probably a few late-night debugging sessions.” But when I started experimenting, I was surprised to find that setting up a local model—or renting a cloud GPU—was often easier than dealing with some so-called “productivity agents” that promise magic but require five browser extensions just to install.

LM Studio felt like the “VS Code for local LLMs.” I installed it, opened it up, and was greeted with a catalog of models. No Docker compose files, no YAML forests—just a search bar and a download button.

My first test? Mistral 7B. I searched for it, hit download, and within minutes, I was chatting with the model locally. No latency, no data leaving my machine. Next, I tried Llama 2 (13B parameters). The process was the same: search, download, and wait for the initial setup (which took about 5 minutes on my M2 MacBook Pro).

Once a model was downloaded, I could:

For lightweight tasks like note-taking or quick analysis, this was more than enough. But I also tested image generation with Stable Diffusion 2.1. On my laptop, generating a 512x512 image took ~20 seconds, and my fan sounded like it was about to take off.

The other side of the experiment was Runpod. I wanted to see if renting a cloud GPU could handle heavier workloads—like generating high-res images or running larger LLMs—without my laptop overheating.

The process was straightforward:

Once the pod was up, I could run containers, host APIs, or even train models. The best part? No need to buy a GPU for weekend experiments—I could spin it down when done and only pay for the time I used.

I put both platforms through their paces to see how they stacked up:

For me, it’s not either/or:

The funny part is that in both cases, getting something useful running was often easier than dealing with some “productivity agents” that promise magic but require five browser extensions and a small ceremony to install. I tried one recently—just to see—and the installation process involved more steps than setting up LM Studio or Runpod.

As someone who’s spent time in security—especially as a CISO—I care about control, visibility, and avoiding single points of failure. Here’s why local LLMs or rented GPUs are interesting from that perspective:

Long term, I like having both options. Just like in networking, it’s about picking the right tool for the job—and understanding enough about what’s under the hood that you’re not surprised when things scale, break, or need to be secured properly.

Post #3 · · Home Lab / Network Security

Over time I ended up with a lot of “always-on” devices: smart plugs, lights, outlets, an alarm clock, speakers, TVs — the usual modern home stack. When I started doing packet captures on my home network, it was obvious these devices generate steady background traffic (DNS lookups, NTP time sync, cloud telemetry, periodic update checks, and a good amount of broadcast / multicast chatter).

None of that is automatically “bad,” but it creates two problems: visibility gets noisy, and the blast radius grows. If any single IoT device is compromised, a flat home network makes it easier for that compromise to pivot laterally.

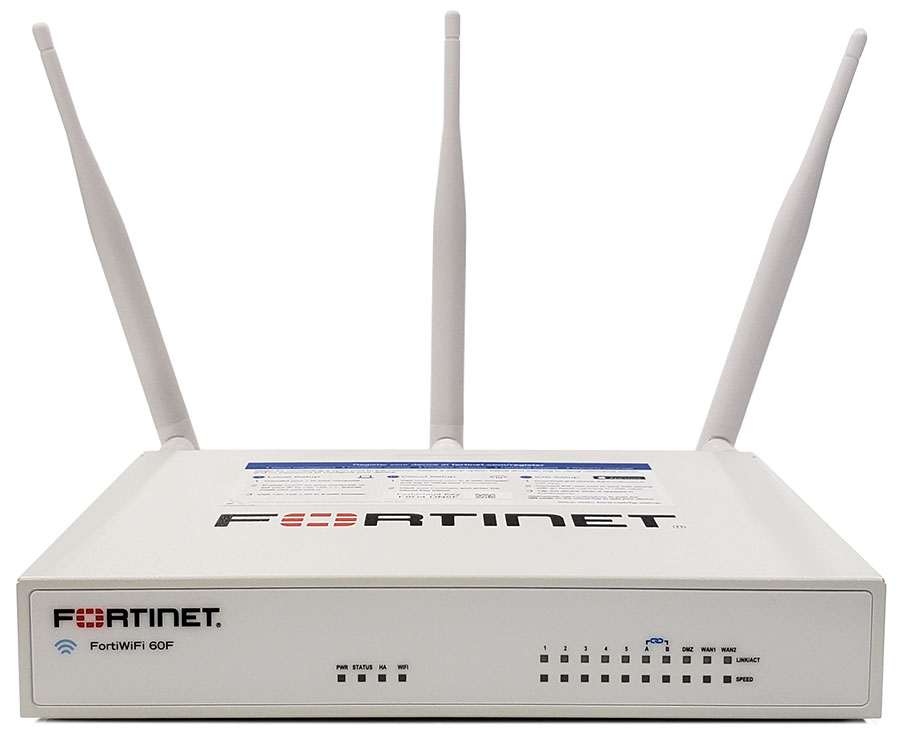

I chose a FortiWiFi 60F so routing, Wi-Fi, and policy enforcement could live in one place. I created a dedicated IoT SSID treated like its own security zone, then built firewall rules around a simple principle: deny by default, allow only what’s needed, and log the rest.

The main friction point was that several devices were 2.4 GHz-only and fairly picky about “legacy-friendly” Wi-Fi settings. A few would fail to join, or would join and drop intermittently. The fix was to tune the IoT SSID for compatibility.

After devices were stable on the new SSID, the security work was mostly policy design. I used a simple policy stack:

The biggest win was clarity. My trusted network captures became quieter and more meaningful, and any noisy or unusual IoT behavior is now scoped to its own segment. The second win is risk management: even if a device is vulnerable, it’s fenced into a network that can’t freely reach the rest of the house.

Post #6 · · Windows / Security

Sometimes, the most interesting discoveries start with a simple message from a customer.

Recently, a customer reached out reporting a potential vulnerability related to unquoted service paths. Curious, I decided to investigate — and to my surprise, I was able to reproduce the issue exactly as described. It was a moment that reminded me how even well-known bugs can surface in unexpected places.

For those unfamiliar, the unquoted service path vulnerability is a classic Windows misconfiguration. When a service executable path includes spaces and isn't wrapped in quotation marks, Windows may misinterpret the command. This can lead to unintended execution of malicious files if they're planted in predictable paths.

For example, if a service is registered like this:

C:\Program Files\Vulnerable Service\Service.exeWithout quotes, Windows will first attempt to run:

C:\Program.exeC:\Program Files\Vulnerable.exeC:\Program Files\Vulnerable Service\Service.exe

If an attacker can place a malicious Program.exe in C:\, it might get executed instead — but only if they already have elevated privileges to write to those directories.

Using the steps outlined in this GitHub guide, I set up a test environment with:

Service.exe dropped into the pathAfter restarting the service, my dummy code executed successfully — validating the vulnerability in this (misconfigured) scenario.

This got me digging further and I came across this insightful blog post by Raymond Chen at Microsoft: 👉 Unquoted service paths: The new frontier in script kiddie security vulnerability reports

Raymond walks through multiple examples of poorly understood — and sometimes outright false — vulnerability reports. Some of these reports flagged unexploitable issues, such as:

C:\ProgramData or C:\Windows\System32His conclusion? Quoting paths is best practice, but most of these scenarios are not exploitable unless the system is already misconfigured.

This was a great reminder that:

Fixing these issues takes minutes — but not fixing them can lead to hours of explaining why they weren’t a risk …until they were.

Post #5 · · Entrepreneurship / Defense Tech

When I joined the National Security Innovation Network (NSIN) through the FedTech Foundry program, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. All I knew was that I was being paired with a team and a Department of Defense researcher — someone who held a promising patent — and together we’d explore how to turn that invention into a viable, real-world product. We were competing with other teams for a shot at a grant to help launch a startup and bring our prototype to life. But as I quickly learned, the experience was far more than a competition — it was a crash course in innovation, pivoting under pressure, and understanding what real customer discovery looks like.

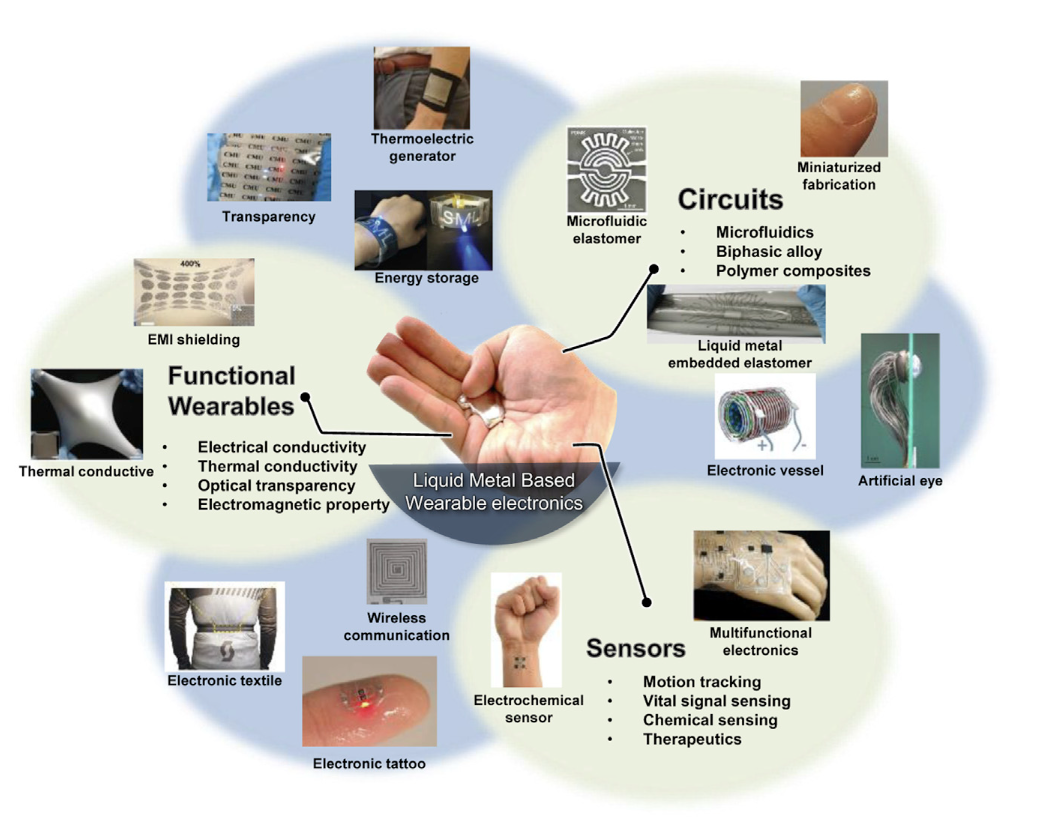

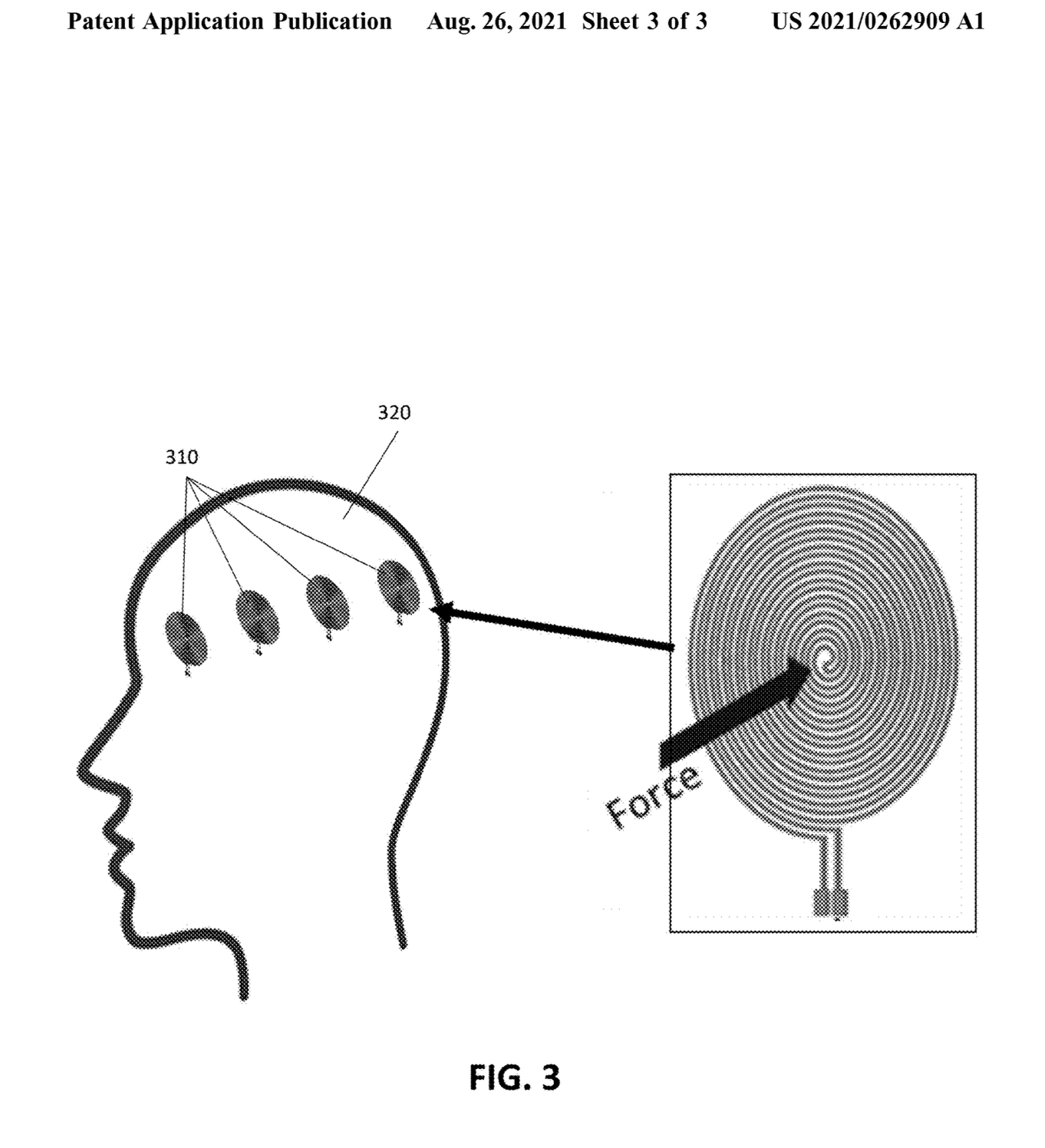

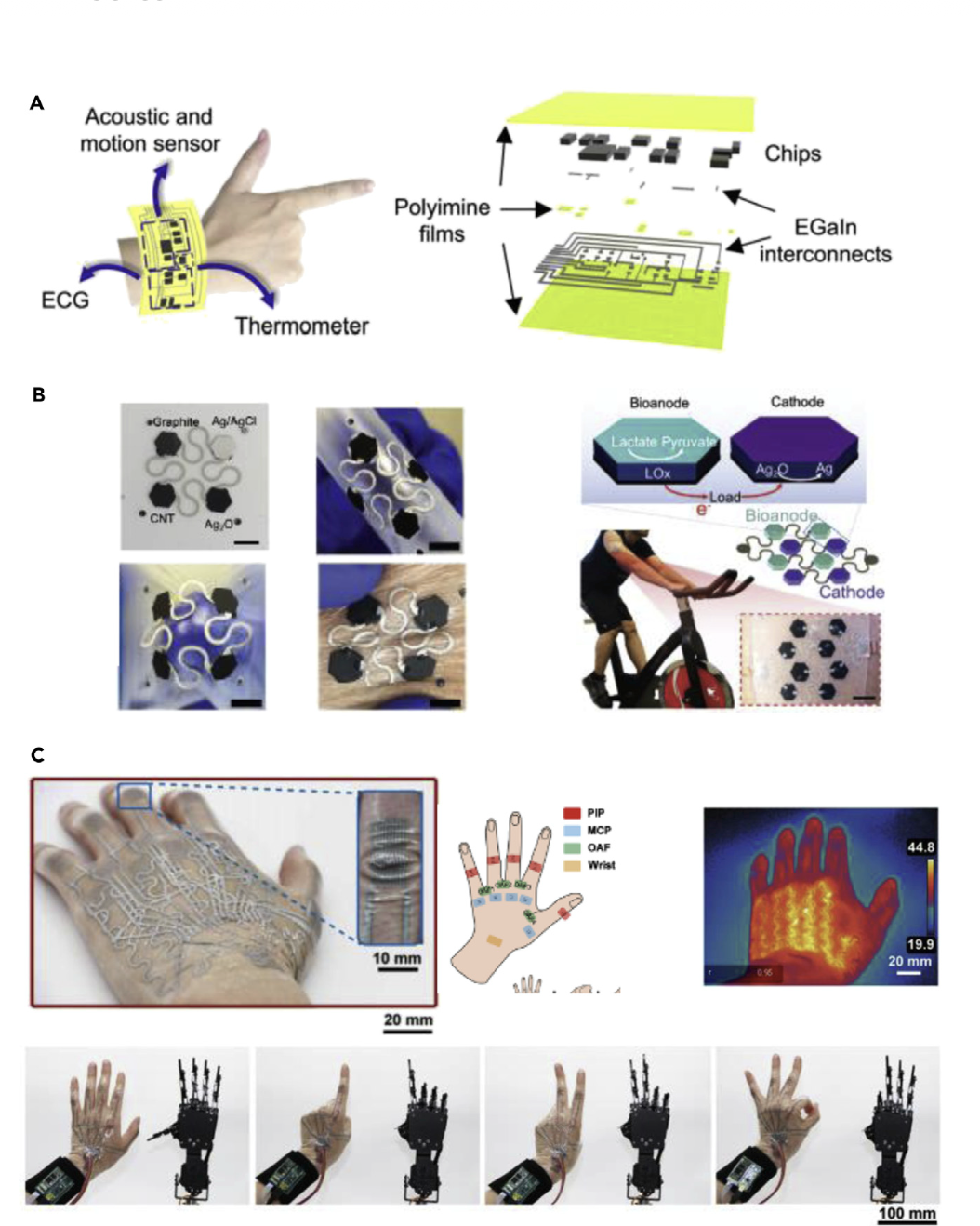

Our team was assigned a fascinating piece of tech: a liquid-metal-based flexible silicone sensor embedded with soft materials. Unlike traditional rigid sensors, this one was stretchable, biofidelic, and could be embedded into soft materials to detect high-impact forces — think milliseconds-scale blast events or pressure changes. The original idea? Apply it to NFL helmets, helping detect concussions by measuring internal forces during impacts. It seemed like a great fit — literally and metaphorically.

But as we began interviewing potential users, especially within the Department of Defense, our thinking evolved. Through conversations with Air Force pilots, we discovered an entirely different — and possibly more impactful — use case: integrating the sensor technology into flight suits. The sensor’s ability to deform with the material and remain sensitive during extreme conditions made it a strong candidate for monitoring pressure, strain, and potential injuries in high-G or crash scenarios. This pivot not only changed our direction — it changed our mindset. We weren’t just repurposing technology; we were solving real operational pain points with defense relevance.

With insights from military interviews and technical specs from the patent, we worked on positioning the flexible sensor as a platform technology. Potential applications ranged from:

While we didn't advance to the final grant round, our team was proud of the prototype concept and the groundwork we laid for future development.

Although we didn’t take home the top prize, I walked away with something just as valuable:

The FedTech Foundry is more than a startup incubator. It's a proving ground — one where the process matters just as much as the product.

Innovation isn’t linear. Sometimes the best ideas emerge when you're forced to stretch — to reconsider assumptions, change direction, and build something that resonates with a user’s actual needs. That’s exactly what this experience gave me: the ability to stretch, adapt, and grow — not just as a team member, but as an entrepreneur.

Post #7 · · Home Lab / Network Security

This was not a dramatic “caught a hacker” story. It started with me doing the boring thing I try to do after any change in my home lab: baseline traffic captures and sanity checks.

I had recently tightened segmentation between my Trusted LAN and my IoT segment, and I was in the middle of testing a new smart outlet I bought online. Cheap, feature rich, and the kind of thing you convince yourself is fine because it is just a plug.

The outlet joined WiFi, the companion app paired quickly, and everything looked normal until I glanced at my capture. One device was reaching out to a public IP I did not recognize: 221.233.52.33. That was enough to slow me down and switch from “setup mode” to “verify mode.”

IoT devices talking to the internet is not automatically suspicious. Firmware checks, time sync, cloud control, telemetry, all of that exists. What I pay attention to is consistency, timing, and whether the destination makes sense for the device and for how I intend to use it.

I do not label something as malicious just because it feels weird. I try to turn “weird” into a short list of testable questions. Who is talking. To where. How often. And does it stop when I remove cloud dependencies.

I keep this routine simple so I will actually do it every time.

1) Prove it is the outlet, not some other device

2) Focus on the one external destination that triggered the question

ip.addr == 221.233.52.33dns then inspect query names near the same timestamps.3) Identify protocol and port so you know what you are dealing with

tcp.port == 443 && ip.addr == 221.233.52.33At this point I was not trying to “decrypt the traffic” or prove attacker intent. I only needed enough clarity to decide whether to isolate the device and test what breaks when outbound access is restricted.

Before I called it “sketchy,” I ran the same three pivots I always run: confirm device identity, confirm the egress path, and confirm whether the behavior is required for the features I actually want.

1) Confirm the outlet identity via neighbor tables

arp -aarp -an or ip neigh2) Confirm it is not bypassing your DNS visibility

3) Test what happens when you block the destination

221.233.52.33 for the IoT segment.

The IP address 221.233.52.33 stood out for another reason - its geolocation. When I ran a quick whois check:

$ whois 221.233.52.33

...

origin: CN

country: CN

...This confirmed the IP was located in China, a country known for state-sponsored cyber operations targeting Western infrastructure. I then cross-referenced this with my local threat intelligence feed using:

$ mtrg -r 221.233.52.33

...

[Threat Intelligence Match]

IP: 221.233.52.33

Type: C2 (Command and Control)

Associated Groups: APT41, Winnti

...While this wasn't definitive proof of malicious activity, it was enough to significantly raise my suspicion level. Chinese actor groups are known for:

The consistent outbound connections to this Chinese IP, even when I wasn't interacting with the outlet, matched known APT behavior patterns.